When was the last time you thought about language? Being able to communicate with others we encounter is of critical importance on any given day. Language itself, however, is not something many of us consider outside the realms of academics or literature until we are beyond the boundaries of our own tongue. Travelers often have to rely on hand gestures, humility, and faith that messages are understood when in a foreign place. This is something I was recently reminded of at a Vietnamese train station. I was able to find the right train but have no idea what details were lost in the process of seeking directions. The lack of understanding is compounded when you’re not only dealing with a different tongue but also a different alphabet. When visiting a foreign country, learning the requisite “Hello,” “Thank you,” “Please,” and “Where is the toilet?” is very important but will only get you so far. (Though I have seen how stumbling through “Happy New Year” in Vietnamese before Tet is sure to bring a smile to local faces. Small efforts almost always bring great rewards.) Yes, a certain level of misunderstanding is to be expected in travel.

No parking? Do not enter? When traveling to Cambodia, where the alphabet is different, I was not only not able to read the signs but could not sound the words out to ask others what they meant either. It is a humbling experience. Thankfully helpful people exist all over the world, so I was able to get by without being able to read the signs.

Our world is encapsulated in an intricate web of words that has shaped our history and defines our present existence. One of the grave consequences of the age of globalization is the loss of languages in cultures worldwide. How do people navigate the language differences within a community or home as a modern language becomes the dominant one? It’s not just the ability to have a discussion that dies with this decline. There is also a disconnect from heritage and environment that is at some point irreparable.

While none of us are immune, indigenous peoples run the greatest risk of this loss as they become more connected with roads, devices, and the lure of cities for building a different life for their youth. Thankfully there are people dedicated to the importance of words and who are working to preserve some of these languages and the deeper meanings that are connected to them.

A young Waorani girl outside her home in Guiyero. She will no doubt see many changes to her village and way of life as she grows.

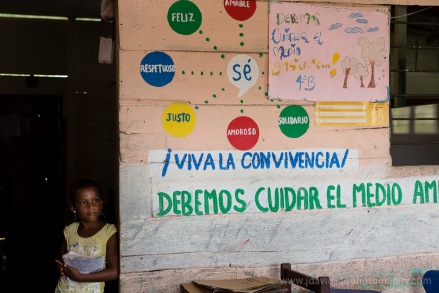

The Yasuní region of Ecuador is a region undergoing rapid change. The Waorani that live there are varied in their level of contact with the outside world. Some are completely isolated from modern culture, living as they have for centuries. On the other side of the spectrum are the villages along the “Via Auca,” an oil road built in the 1950’s that brought with it modern conveniences, medical care, industrialized foods, and eventually, tourism. Between these two extremes, there are communities working on the transition that is sure to come. Last summer I visited three of these villages, Guiyero, Ganketapare, and Timpoka, that lie along a road built in the 1990’s. The way of life in these villages is a hybrid, though mostly traditional one. Spanish is widely spoken but is freely interchanged with the native Wao Tededo. Hunting is done with guns as well as blowguns and spears. Western clothes and cell phones are a reality. Tourism is certainly on its way but has not yet arrived. This is a tremendous time of transition and opportunity for the Waorani people.

The Waorani village of Guiyero, like the culture itself is evolving. Traditional straw structures stand next to modern buildings.

I was in this area with Megan Westervelt who has been working with the Waorani since August 2014. With cameras on loan from Ohio University, she has provided these communities with a visual voice. As she teaches them about composition and some basic technical aspects of photography, she also talks of how to tell a story about their lives through images. During my short visit, people from the communities met with us daily to work with the cameras and look at photos. Nods and chatter filled the room as they talked about the different stories they could tell. Our discussions with the group centered around parts of their lives that may seem mundane or normal to them but are unique to their culture. (The challenge of showing “normal” moments in a way that is interesting is one that many a photographer has faced.) The resulting images were soulful and intimate. Megan and these communities compiled the images, and with the support of several groups in Ecuador and a successful Kickstarter campaign, they were showcased in Wao Mimo: Yasuní Bajo el Lente Waorani, an exhibit that traveled to Quito and Coca last fall.

Megan Westervelt talks to a group of Waorani about elements in a photo essay. She has encouraged these communities to tell their stories through photography as a way to share their unique ways of life with others.

During the time that Megan has worked with the communities in the Yasuní, she has fostered relationships with the Waorani, not only taking on the role of teacher and advocate, but of friend.

While we were visiting the communities in the Yasuní, I met Marleen Haboud, a professor of linguistics from Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador (PUCE) and director of Oralidad Modernidad. She works with minority groups to help them to preserve and revitalize their native language. The projects she’s involved with are multi-faceted and include mapping changes in language over generations as they evolve from the native tongue, to Quechua, and eventually Spanish. In some homes she has met families where grandparents have no way to communicate with their grandchildren because there are three distinct languages spoken. Verbal understanding lost in three generations…under one roof. It is a tragic byproduct of progress.

Marleen Haboud and Juan Carlos Armijos talk to a group of Waorani about the work that she has done with other tribes in Ecuador.

Wampi Humberto Ahua, a Waorani elder and the leader of the community, tells a story about hunting to the group. These stories are filmed so they can be translated and eventually become material for animated films that will be given back to the community.

Marleen’s work extends beyond words. She works with the stories told in these cultures in an effort to preserve heritage along with language. One facet of the work, Así Dicen Mis Abuelos (So my Grandparents Say), is a collaboration with her filmmaker daughter. I was able to witness the beginning of this process in action. Dozens of Waorani gathered in a room. Elders in the community were asked to come forward and tell a story. As they talked, they inevitably became animated while everyone watched and listened, gathered on the floor and in chairs around them. Marleen and her team filmed the storytelling. As I listened to words I could not understand, my mind pictured stories like these being told in villages for centuries, around campfires or while doing daily tasks. With the plotlines fresh in their minds, the Waorani gathered in groups to illustrate the stories. It is very important for Marleen to know what aspects of the stories look like visually for each tribe she works with. On this particular day, one man’s story was about hunting with a blow gun. Without the drawings to accompany the words, it would be difficult to know exactly what Waorani darts and blowguns look like, a key detail in getting the story right. With the recordings and illustrations in tow, Marleen and her daughter work with representatives from the villages to help with translation. The final products include animated films and books depicting the story in Wao Tededo (in this case) with Spanish subtitles. These resources are given back to the communities and serve as an invaluable tool for educating their children in both the content of the stories and the language. The beauty of this exercise was not just in what was being produced but also in the spirit of community and sharing that grew as people from several generations talked, drew, and laughed together.

After elders told their stories, Omaca Gloria Irumenga joined others in the room drawing their interpretations of the tales. These illustrations are valuable tools to help Marleen produce resources to give back to the community in the form of animated films.

I could write multiple posts about the work that both Megan and Marleen are doing in Ecuador. What I witnessed was only a few short days, a small glimpse into labors of passion that no doubt will continue for the span of their lifetimes. They certainly have huge challenges ahead, but I believe their impact is taking root in these villages as young and old take pride in who they are, where they come from, and the importance of keeping some of that heritage alive.

It is clear that the intentions of these two women are not to keep the modern world away from the Waorani. Often when I travel with groups of tourists to indigenous villages, comments arise about how strange it is that the people there have cell phones or TVs. Isn’t it natural that these luxuries would be attractive to them? Dismay that people enjoy modern conveniences because of the quaint or romanticized images we, as travelers from first-world countries, have in our minds about their culture is short-sighted and self-centered. Expecting them to stay as they have been historically is no different than wanting to put them behind glass, on a shelf in a museum, frozen in time. No, the goal in these projects is rather helping the Waorani to recognize their uniqueness, with their language and their ways of life, while their communities welcome the 21st under their own terms.

Preserving culture by giving people voices through the arts: photography and drawing are two ways that Megan and Marleen are working with the Waorani to tell their story. Carolina Ahua’s (L) photographs were included in the Wao Mimo exhibit in Quito and Coca. Wampi Humberto Ahua (R) draws a detail of the darts he mentioned in the story he shared with the group.

In the months since my visit to the Yasuní, ideas about language and culture have swirled in my mind. (I hesitate even now, putting words to this since much of it is at best half-baked.) I’ve visited with members from Haida (Haida Gwaii, British Columbia) and Tlingit (Alaska) tribes who are going to great lengths to learn the tongue of their ancestors and carry on the knowledge that has long been known in their culture. Friends who work with Native Americans have told me of the gravity in elders’ voices as they describe all that is lost when words are lost. In one tribe, an elder explained that a tree might be “tree’ in English, but in their native tongue there are numerous words used, each that carries a significant meaning associated with its role in the environment. All of that meaning disappears when “tree” is used instead.

For centuries, the people of Haida Gwaii have spread knowledge through stories. These originated in nature and were told through art. Today, Linda Tollas (L), who helped design the Spirit Lake Trail near Queen Charlotte City, educates visitors in regards to native use of the forests, for food and medicine. Christian White (R) continues his family’s heritage of telling stories through art in Old Masset.

We don’t have to look to another group of people to see the ramifications of this concept. Every year, words are officially added and removed from dictionaries as they become relevant or obscure in modern culture. Last year in the Oxford Junior Dictionary, MP3 player and blog were added while heron and mistletoe were removed. While a children’s dictionary is not an official lexicon, it does speak to where we are headed. Aside from pocket groups, how many in my generation understand the words associated with growing, harvesting, and canning food, darning socks, or sewing, much less how to put them to use? How many in the next generation will know how to read a map or cook without a microwave? Our world is rapidly changing, and as it does, the way in which we relate to each other is morphing too. Are we taking the time to think about what parts of our own culture are worth holding onto in the process of our evolution? Who are the Megan’s and Marleen’s speaking out for all of us?